Resumen

La rehabilitación de los centros históricos de México y Panamá fueron el resultado de una estrecha colaboración entre el sector público y el privado, comprobando que esta estrategia es viable y con gran potencial de sostenibilidad, siempre y cuando se logre un balance entre las necesidades sociales y la presión del mercado.

Introducción

En esta presentación mencionare algunos casos relacionados a la preservación de centros históricos en América Latina, unos más exitosos que otros, pero todos con lecciones que ofrecer.

Centro Histórico de la Ciudad de México

El centro Histórico de México sufrió un lento declive a lo largo del siglo XX, dejando de ser un centro vital y cosmopolita con gran vida artística, intelectual, comercial y política, y con una población de aproximadamente 90,000 personas, para convertirse en un lugar deteriorado, plagado de crimen, con muchos edificios abandonados y una población reducida a 5,000 habitantes. Una serie de eventos iniciaron y aceleraron este proceso, comenzando con las leyes de control de alquileres de la década de 1940 que inhibieron la inversión de los propietarios en el área, la salida de la universidad (UNAM) de sus edificios del campus central en la década de 1950, recesiones financieras y finalmente, el devastador terremoto de 1985 que destruyó o dañó seriamente más de 400 edificios en el centro de la ciudad, muchos de los cuales permanecieron sin reparar por muchos años.

La inscripción del centro Histórico de México en la Lista de Patrimonio Mundial en 1987, el establecimiento de la Sociedad de Amigos del Centro Histórico, la creación del Fideicomiso del Centro Histórico en 1990 y el ofrecimiento de incentivos fiscales, marcaron el inicio de una lenta recuperación, pero no fueron suficientes para atraer una significante inversión en el Centro Histórico.

El conjunto de acciones que finalmente detonaron la rehabilitación del Centro empezó en 1999 con la invitación de López Obrador, entonces Alcalde de México, a Carlos Slim[1], el hombre más rico de América Latina, a invertir en la revitalización de la Avenida Reforma, la cual había sido severamente dañada por el terremoto. Slim hizo una contrapropuesta, ofreciendo invertir en el Centro Histórico siempre y cuando la Presidencia de la República, apoyara la iniciativa. Meses después, el Presidente Fox anunció la creación de un Consejo Consultivo, con Slim a la cabeza de su Comité Ejecutivo, conformado por más de 100 representantes de la sociedad civil y autoridades pertinentes. El Consejo elaboró un plan de acción y el Gobierno Federal creó un Fondo de Obra Pública para financiar infraestructura y seguridad, mientras que la Municipalidad se encargó de rehabilitar calles, enterrar cables, y realizar otras mejoras urbanas. Estas acciones sumadas a nuevos incentivos fiscales y el compromiso de inversión de Carlos Slim, finalmente detonaron la inversión privada en el centro y su eventual revitalización[2].

Paralelamente, Slim estableció la Fundación del Centro Histórico, una entidad sin fines de lucro, con el fin de implementar los objetivos sociales y culturales del plan de acción. De esta manera, mientras que el sector público mejoraba las calles, la seguridad y los espacios públicos, los inversionistas privados recuperaban los inmuebles y la Fundación apoyaba programas culturales, de salud, de educación y otorgaba microcréditos en beneficio de la población local[3].

Este sistema de colaboración tuvo visibles resultados luego de 5-6 años, incluyendo la creación de miles de puestos de trabajo, la rehabilitación de cientos de edificios, y el incremento del turismo y la población del Centro Histórico. Si bien el Consejo Consultivo dejó de tener un papel determinante, las inversiones públicas y privadas en el Centro Histórico continuaron hasta la fecha.

Actualmente, el Plan Integral de Manejo del Centro Histórico de la Ciudad de México (2017-2022), sigue priorizando la participación del sector privado, y la inclusión de Asociaciones Público-Privadas en la gestión y el financiamiento de fuentes privadas en la ejecución de sus estrategias de desarrollo y revitalización.

Sin embargo, el plan reconoce que “la deficiente formalización de la propiedad constituye uno de los principales obstáculos para aplicar programas de mejoramiento físico de los inmuebles, otorgar certeza en las operaciones inmobiliarias y atraer y aplicar beneficios fiscales”.

Asimismo, busca proporcionar certidumbre jurídica y claridad normativa que posibilite las condiciones óptimas de recuperación y conservación de los bienes patrimoniales. [4]

Adicionalmente, el Plan de Recuperación 2020-2024 del Centro Histórico de México incluye un programa de vivienda e inversión privada. [5]

Casco Antiguo de Panamá

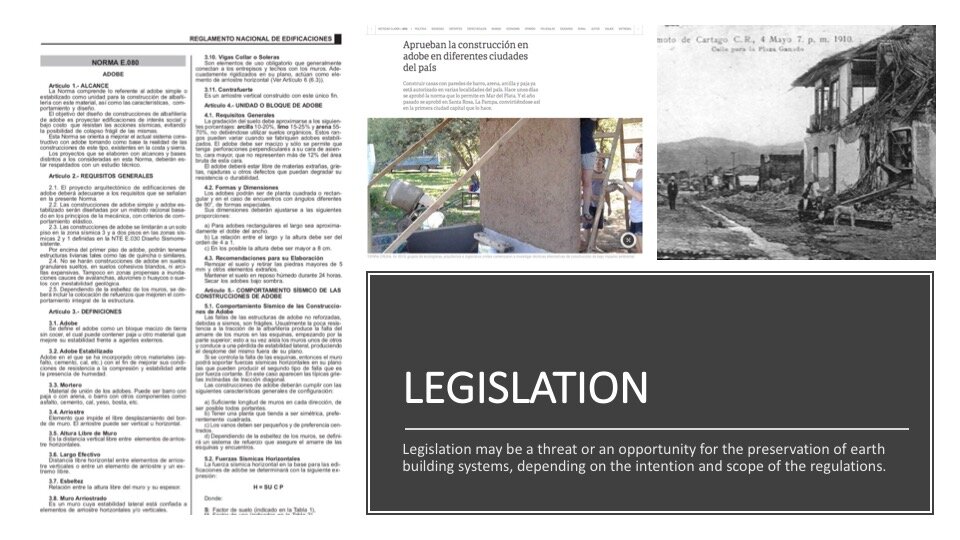

El Casco Antiguo de Panamá fue inscrito en la Lista de Patrimonio Mundial en 1997 y en 1999 el Canal fue entregado a Panamá lo que generó un boom para los inversionistas en el país. Sin embargo, el centro histórico estaba en muy mal estado de conservación y con problemas de crimen y violencia. Luego de su declaratoria, el gobierno estableció el decreto Ley 9 de 1997 [6] (modificado en 2013[7] y 2017) el cual ofreció (durante un plazo de 5 años) los siguientes incentivos para promover la inversión en el Casco Antiguo[8]:

· Préstamos de bajo interés para comprar y restaurar propiedades o construir nuevas edificaciones en el Casco Antiguo (“Préstamos Hipotecarios Preferenciales para Restauración”);

· Exención del impuesto de transferencia de propiedad;

· Exención del impuesto sobre la renta;

· Exención del impuesto predial (por 30 años);

· Exención del impuesto de importación sobre materiales y equipos de construcción.

Pero tan o más importante que los incentivos fiscales, la ley incluye cláusulas clave como el establecimiento de diferentes niveles de valor arquitectónico/histórico para las propiedades incluidas en la zona protegida. De acuerdo a esta categorización, los requerimientos de conservación varían de la conservación integral para los inmuebles o partes de inmuebles de gran valor, hasta una casi completa libertad de acción sólo limitada por las reglas de zonificación, para los inmuebles o partes de inmuebles de poco valor arquitectónico o ambiental. Otra cláusula importante es el establecimiento de un límite de 15 días para la revisión de propuestas de intervención por parte de la Dirección de Patrimonio Histórico, y otros 15 días para la emisión de su respuesta. De no cumplirse estos plazos, la propuesta es considerada aprobada.

La ley también incluye incentivos para arrendatarios, apoyo técnico para residentes que deseen comprar/restaurar sus viviendas, y sanciones de hasta $150,000 para los propietarios de inmuebles desocupados o deteriorados, que no reviertan esta condición dentro de un plazo de 2 años a partir de la promulgación de la ley.

Esta legislación creó un ambiente propicio para inversionistas como la empresa Conservatorio S.A.[9] fundada por dos abogados, quienes desde el 2005 trabajan en proyectos de renovación y construcción en el Casco Antiguo de Panamá.[10] Esta empresa, certificada como B Corp o Corporación B, no solo busca el retorno financiero para sus inversionistas sino la preservación de la diversidad y la sostenibilidad del ecosistema urbano del centro.

Para esto, ha desarrollado una filosofía, llamada "Revitalización Urbana Sostenible" (SUR) la cual es evidente en la amplia combinación de productos y el enfoque de la compañía para seleccionar inquilinos y fomentar la propiedad de viviendas. Conservatorio vende unidades residenciales, fomentando la propiedad local, y alquila propiedades comerciales, favoreciendo a inquilinos independientes sobre cadenas comerciales. La cartera de propiedades de Conservatorio mezcla unidades de alta gama con viviendas, oficinas, hoteles y tiendas asequibles, e incluye recursos comunitarios como galerías, teatros e incubadoras de empresas.

SUR es una estrategia creada por una empresa privada para mitigar las externalidades negativas de la renovación y promover resultados sociales positivos. Actúa en contra de las tendencias de homogeneización cultural y gentrificación que a menudo acompañan al desarrollo. Para tener una influencia positiva en los vecindarios, SUR promueve la equidad construyendo una unidad de vivienda asequible por cada unidad de mercado de alta gama. Los dos tipos de apartamentos están construidos con los mismos estándares de calidad, pero difieren en comodidades como estacionamiento, número de habitaciones y ubicación dentro de un complejo.

Además, Conservatorio dedica el 1% en cada proyecto a iniciativas de impacto social que han sido identificadas y articuladas a través de talleres participativos con comunidades locales utilizando una metodología llamada "LiderazCo" que la compañía desarrolló con el Laboratorio de Innovadores Comunitarios del Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). En colaboración con los residentes, Conservatorio:

· Investigó e implementó el programa de intervención social multisectorial “Santa Ana Lidera” que, con una subvención de USAID, atrajo a cinco ONGs para abordar necesidades sociales críticas específicas identificadas por la comunidad de Santa Ana;

· Ejecutó intervenciones de urbanismo táctico, como una parada de autobús saludable (La Parada Sana) y jardines comunitarios;

· Rehabilitó un espacio de reunión comunitaria en el Hotel Santa Ana;

· Fundó el programa de reintegración de pandillas “Esperanza San Felipe” que ofrece, a cambio de un compromiso de rechazar la violencia, una capacitación laboral intensiva de 12 semanas con oportunidades de colocación y financiamiento inicial para nuevas empresas[11];

· Diseñó el Centro de Innovación Urbana “La Manzana” para ONGs, instituciones académicas y emprendedores sociales.

Sin embargo, a pesar del impacto positivo que la legislación tuvo en la rehabilitación del Casco Antiguo de Panamá, de acuerdo a K.C. Hardin, CEO de Conservatorio S.A., la ley falló en estos aspectos:

· Creó un mecanismo de desplazamiento sin proporcionar un mecanismo de contrapeso para la inclusión (por ejemplo, fondos para viviendas sociales).

· No incluyó medidas adecuadas para prevenir la especulación. Incluye una cláusula que pretende imponer multas si las propiedades no se desarrollaban dentro de dos años, pero todos sabían que dos años es apenas tiempo suficiente para que se aprueben los planes, por lo que nunca se aplicó. El sistema debería haber sido calibrado para proporcionar más incentivos a aquellos que actuaban más rápido y menos a aquellos que mantenían la propiedad sin desarrollar para venderla por un precio más alto.

· La ley original creó una oficina del Casco Antiguo, pero no le dio el poder necesario para administrar la zona, ni los medios para generar los recursos que necesitaba para realizar su trabajo. Como resultado, existen diez instituciones diferentes que se estrangulan entre sí, y ninguna con fondos o incentivos para responder a las necesidades especiales del área[12].

Centro Histórico de Lima

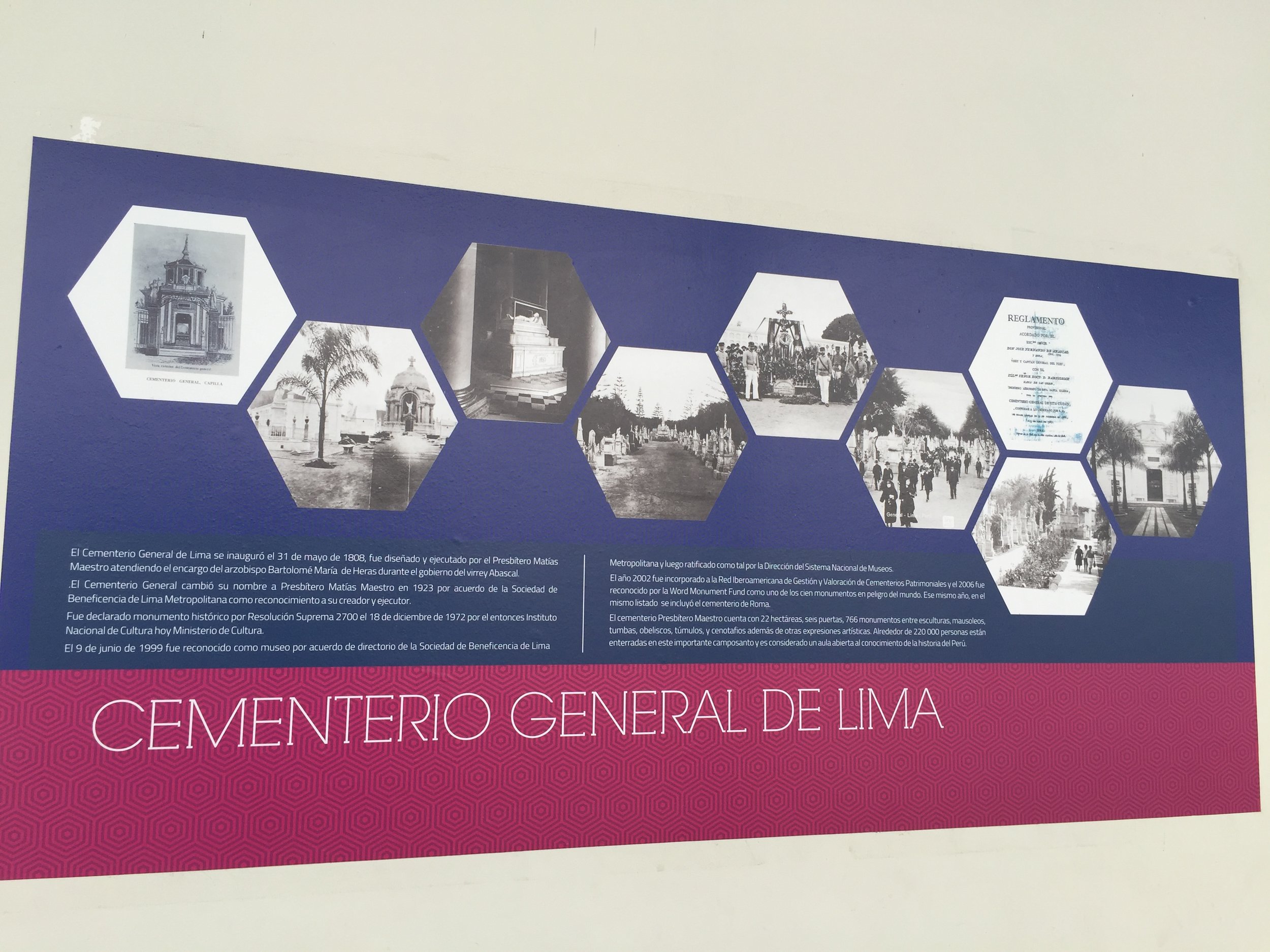

El Centro Histórico de Lima o Ciudad de los Reyes, forma parte de la Lista de Patrimonio Mundial desde 1988[13]. A pesar de su gran valor patrimonial, aproximadamente dos terceras partes de sus inmuebles están en regular o mal estado de conservación, posee un déficit en espacios verdes y sufre de contaminación ambiental, del ruido y de residuos sólidos.

El “Plan Maestro del Centro Histórico de Lima al 2029 con visión al 2035”, elaborado por PROLIMA (Programa para la Recuperación del Centro Histórico de Lima) propone revertir la actual situación del CHL mediante una recuperación integral de la ciudad, con miras a impulsar la inversión privada y nuevas oportunidades de trabajo y de vida para los vecinos, y a generar mejores condiciones habitacionales que permitan un desarrollo social sostenible.[14]

En Junio 2021, en colaboración con Juan Pablo de la Puente y Elías Mujica, coordinamos un taller en formato “mesa ejecutiva” sobre la participación privada en la gestión del patrimonio en el Perú. El taller, financiado por la Unión Europea como parte de un proyecto que buscaba fortalecer la gestión del patrimonio cultural del Centro Histórico de Lima, contó con la participación de importantes actores del sector privado y estas son algunas de sus conclusiones: [15]

1. El Perú es un país extremadamente rico en patrimonio cultural pero el presupuesto público del sector cultura es extremadamente limitado, por lo que el Estado debe reconocer que por sí solo no puede proteger y gestionar el patrimonio cultural.

2. Al momento de tomar decisiones sobre inversiones en torno al patrimonio cultural, priman más los criterios ideológicos y subjetivos, por sobre los de eficiencia (sustentos y necesidades técnicas). Asimismo, hay limitaciones en materia de capacidades técnicas y de gestión en el sector cultura.

3. La gran mayoría de los inmuebles virreinales y republicanos son de propiedad privada, sin embargo, la gran mayoría de los beneficios e incentivos existentes aplican a los monumentos de propiedad del Estado. Si no existen incentivos positivos para los propietarios, será muy difícil alcanzar la preservación del monumento.

4. Es necesario fomentar una relación virtuosa entre turismo y patrimonio.

5. En el Perú se han desarrollado diferentes modelos de gestión del patrimonio cultural en los que el sector privado ha tenido un rol preponderante. Existen modelos exitosos que pueden y deben replicarse, pero hace falta una regulación que incentive y no obstaculice el rescate del patrimonio desde lo privado. Es necesario convertir las buenas prácticas en políticas de Estado.

6. La normativa existente contempla procesos y plazos que no se adecuan a la dinámica empresarial. En muchos casos la fábrica no siempre coincide con lo detallado en Registros Públicos lo que implica entrar en un oneroso proceso de regularización de fábrica. Es necesario flexibilizar la norma, para que esté más cerca al empresario y al inquilino.

7. La falta de toma de decisiones oportunas en el sector público causa la demora, o en muchos casos, la pérdida de oportunidades, para el financiamiento de la recuperación y gestión del patrimonio cultural. Es necesario implementar un proceso de simplificación administrativa para crear plazos y exigir la participación de entidades públicas competentes, para lograr que los procesos no se extiendan innecesariamente.

8. Se debe cambiar la visión que tienen las entidades financieras sobre los inmuebles históricos, en especial los ubicados en el Centro de Lima y promover créditos que contemplen períodos de gracia o plazos amortizables en 15 o 20 años, con tasas razonables.

9. El sistema de asociación público-privada funciona siempre y cuando los actores asuman con responsabilidad el rol que les corresponde y cumplan las reglas establecidas. La participación del sector privado en la gestión del patrimonio es esencial, así como la del sector público en la normatividad y la de la academia, para garantizar la calidad de las intervenciones.

10. Es fundamental la formulación de una ley de incentivos tributarios para la recuperación del patrimonio arquitectónico. Actualmente el sistema genera incentivos perversos que atentan contra el patrimonio, como es el caso de propietarios que prefieren destruir sus viviendas patrimoniales que rehabilitarlas.

Reflexiones Finales

Estos ejemplos demuestran que la participación y la inversión privada en la rehabilitación y gestión de los Centros Históricos en América Latina es considerada una prioridad por los gobiernos y entidades encargadas de su gestión. Sin embargo, en el momento de tratar de involucrar al sector privado de una manera significativa, la realidad puede ser otra.

La subjetividad de criterios, falta de capacidad técnica, falta de incentivos efectivos, incapacidad de convertir las buenas prácticas en políticas de estado, la pérdida de oportunidades a causa de la burocracia, el no cumplir con los roles o responsabilidades asignadas a las instituciones, la informalidad de la propiedad e incertidumbre jurídica y normativa, la especulación, desalojo y la gentrificación, etc. hacen que el loable objetivo de lograr una efectiva colaboración entre el sector privado y las instituciones gubernamentales encargadas de velar por el patrimonio urbano en la rehabilitación y manejo sostenible de los Centros Históricos en América Latina, no sea más que una lista corta de algunos casos exitosos donde los planetas se alinearon por un tiempo y se lograron resultados positivos, en vez de una práctica generalizada e institucionalizada a nivel regional.

Notas

[1] https://realestatemarket.com.mx/arquitectura/25655-el-centro-historico-una-vision-personal-ing-carlos-slim-helu

[2] https://archivo.eluniversal.com.mx/primera/7630.html

[3] https://fundacioncentrohistorico.com.mx/14015-2/

[4] http://maya.puec.unam.mx/pdf/plan_de_manejo_del_centro_historico.pdf

[5] https://www.autoridadcentrohistorico.cdmx.gob.mx/storage/app/media/recuperacion_ch.pdf

[6] https://docs.panama.justia.com/federales/decretos-leyes/9-de-1997-aug-30-1997.pdf

[7] https://www.asamblea.gob.pa/APPS/LEGISPAN/PDF_NORMAS/2010/2013/2013_607_2153.pdf

[8] https://www.linkedin.com/pulse/casco-antiguo-panama-benefits-investing-garc%C3%ADa-de-paredes/

[9] https://www.conservatoriosa.com/

[10] http://heritagefinance.org/case-study/CHiFA-CaseStudy-book.pdf

[11] https://www.globalgiving.org/pfil/16125/projdoc.pdf

[12] Comunicación personal de K.C. Hardin, 22 de abril, 2022.

[13] https://whc.unesco.org/en/list/500

[14] https://aplicativos.munlima.gob.pe/uploads/PlanMaestro/plan_maestro_resumen_ejecutivo.pdf

[15] El encuentro fue grabado y el video se puede bajar en este enlace: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VkfOOLyj3bU